Post by: Netwörkheäd on August 30, 2023, 06:17:53 PM

SUMMARY

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) are releasing this joint Cybersecurity Advisory (CSA) to disseminate QakBot infrastructure indicators of compromise (IOCs) identified through FBI investigations as of August 2023. On August 25, FBI and international partners executed a coordinated operation to disrupt QakBot infrastructure worldwide. Disruption operations targeting QakBot infrastructure resulted in the botnet takeover, which severed the connection between victim computers and QakBot command and control (C2) servers. The FBI is working closely with industry partners to share information about the malware to maximize detection, remediation, and prevention measures for network defenders.

CISA and FBI encourage organizations to implement the recommendations in the Mitigations section to reduce the likelihood of QakBot-related activity and promote identification of QakBot-facilitated ransomware and malware infections. Note: The disruption of QakBot infrastructure does not mitigate other previously installed malware or ransomware on victim computers. If potential compromise is detected, administrators should apply the incident response recommendations included in this CSA and report key findings to a local FBI Field Office or CISA at cisa.gov/report.

Download the PDF version of this report:

For a downloadable copy of IOCs, see:

TECHNICAL DETAILS

Overview

QakBot—also known as Qbot, Quackbot, Pinkslipbot, and TA570—is responsible for thousands of malware infections globally. QakBot has been the precursor to a significant amount of computer intrusions, to include ransomware and the compromise of user accounts within the Financial Sector. In existence since at least 2008, QakBot feeds into the global cybercriminal supply chain and has deep-rooted connections to the criminal ecosystem. QakBot was originally used as a banking trojan to steal banking credentials for account compromise; in most cases, it was delivered via phishing campaigns containing malicious attachments or links to download the malware, which would reside in memory once on the victim network.

Since its initial inception as a banking trojan, QakBot has evolved into a multi-purpose botnet and malware variant that provides threat actors with a wide range of capabilities, to include performing reconnaissance, engaging in lateral movement, gathering and exfiltrating data, and delivering other malicious payloads, including ransomware, on affected devices. QakBot has maintained persistence in the digital environment because of its modular nature. Access to QakBot-affected (victim) devices via compromised credentials are often sold to further the goals of the threat actor who delivered QakBot.

QakBot and affiliated variants have targeted the United States and other global infrastructures, including the Financial Services, Emergency Services, and Commercial Facilities Sectors, and the Election Infrastructure Subsector. FBI and CISA encourage organizations to implement the recommendations in the Mitigations section of this CSA to reduce the likelihood of QakBot-related infections and promote identification of QakBot-induced ransomware and malware infections. Disruption of the QakBot botnet does not mitigate other previously installed malware or ransomware on victim computers. If a potential compromise is detected, administrators should apply the incident response recommendations included in this CSA and report key findings to CISA and FBI.

QakBot Infrastructure

QakBot's modular structure allows for various malicious features, including process and web injection, victim network enumeration and credential stealing, and the delivery of follow-on payloads such as Cobalt Strike[1], Brute Ratel, and other malware. QakBot infections are particularly known to precede the deployment of human-operated ransomware, including Conti[2], ProLock[3], Egregor[4], REvil[5], MegaCortex[6], Black Basta[7], Royal[8], and PwndLocker.

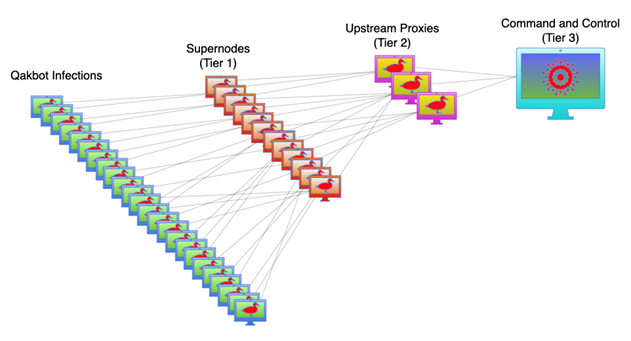

Historically, QakBot's C2 infrastructure relied heavily on using hosting providers for its own infrastructure and malicious activity. These providers lease servers to malicious threat actors, ignore abuse complaints, and do not cooperate with law enforcement. At any given time, thousands of victim computers running Microsoft Windows were infected with QakBot—the botnet was controlled through three tiers of C2 servers.

The first tier of C2 servers includes a subset of thousands of bots selected by QakBot administrators, which are promoted to Tier 1 "supernodes" by downloading an additional software module. These supernodes communicate with the victim computers to relay commands and communications between the upstream C2 servers and the infected computers. As of mid-June 2023, 853 supernodes have been identified in 63 countries, which were active that same month. Supernodes have been observed frequently changing, which assists QakBot in evading detection by network defenders. Each bot has been observed communicating with a set of Tier 1 supernodes to relay communications to the Tier 2 C2 servers, serving as proxies to conceal the main C2 server. The Tier 3 server controls all of the bots.

Indicators of Compromise

FBI has observed the following threat actor tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) in association with OakBot infections:

- QakBot sets up persistence via the Registry Run Key as needed. It will delete this key when running and set it back up before computer restart:

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\ - QakBot will also write its binary back to disk to maintain persistence in the following folder:

C:\Users\\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\ \ - QakBot will write an encrypted registry configuration detailing information about the bot to the following registry key:

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\

In addition, the below IP addresses were assessed to have obtained access to victim computers. Organizations are encouraged to review any connections with these IP addresses, which could potentially indicate a QakBot and/or follow-on malware infection.

Disclaimer: The below IP addresses are assessed to be inactive as of August 29, 2023. Several of these observed IP addresses were first observed as early as 2020, although most date from 2022 or 2023, and have been historically linked to QakBot. FBI and CISA recommend these IP addresses be investigated or vetted by organizations prior to taking action, such as blocking.

IP Address | First Seen |

|---|---|

85.14.243[.]111 | April 2020 |

51.38.62[.]181 | April 2021 |

51.38.62[.]182 | December 2021 |

185.4.67[.]6 | April 2022 |

62.141.42[.]36 | April 2022 |

87.117.247[.]41 | May 2022 |

89.163.212[.]111 | May 2022 |

193.29.187[.]57 | May 2022 |

193.201.9[.]93 | June 2022 |

94.198.50[.]147 | August 2022 |

94.198.50[.]210 | August 2022 |

188.127.243[.]130 | September 2022 |

188.127.243[.]133 | September 2022 |

94.198.51[.]202 | October 2022 |

188.127.242[.]119 | November 2022 |

188.127.242[.]178 | November 2022 |

87.117.247[.]41 | December 2022 |

190.2.143[.]38 | December 2022 |

51.161.202[.]232 | January 2023 |

51.195.49[.]228 | January 2023 |

188.127.243[.]148 | January 2023 |

23.236.181[.]102 | Unknown |

45.84.224[.]23 | Unknown |

46.151.30[.]109 | Unknown |

94.103.85[.]86 | Unknown |

94.198.53[.]17 | Unknown |

95.211.95[.]14 | Unknown |

95.211.172[.]6 | Unknown |

95.211.172[.]7 | Unknown |

95.211.172[.]86 | Unknown |

95.211.172[.]108 | Unknown |

95.211.172[.]109 | Unknown |

95.211.198[.]177 | Unknown |

95.211.250[.]97 | Unknown |

95.211.250[.]98 | Unknown |

95.211.250[.]117 | Unknown |

185.81.114[.]188 | Unknown |

188.127.243[.]145 | Unknown |

188.127.243[.]147 | Unknown |

188.127.243[.]193 | Unknown |

188.241.58[.]140 | Unknown |

193.29.187[.]41 | Unknown |

Organizations are also encouraged to review the Qbot/QakBot Malware presentation from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Cybersecurity Program for additional information.

MITRE ATT&CK TECHNIQUES

For detailed associated software descriptions, tactics used, and groups that have been observed using this software, see MITRE ATT&CK's page on QakBot.[9]

MITIGATIONS

Note: For situational awareness, the following SHA-256 hash is associated with FBI's QakBot uninstaller: 7cdee5a583eacf24b1f142413aabb4e556ccf4ef3a4764ad084c1526cc90e117

CISA and FBI recommend network defenders apply the following mitigations to reduce the likelihood of QakBot-related activity and promote identification of QakBot-induced ransomware and malware infections. Disruption of the QakBot botnet does not mitigate other already-installed malware or ransomware on victim computers. Note: These mitigations align with the Cross-Sector Cybersecurity Performance Goals (CPGs) developed by CISA and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The CPGs provide a minimum set of practices and protections that CISA and NIST recommend all organizations implement. CISA and NIST based the CPGs on existing cybersecurity frameworks and guidance to protect against the most common and impactful threats and TTPs. Visit CISA's Cross-Sector Cybersecurity Performance Goals for more information on the CPGs, including additional recommended baseline protections.

Best Practice Mitigation Recommendations

- Implement a recovery plan to maintain and retain multiple copies of sensitive or proprietary data and servers in a physically separate, segmented, and secure location (i.e., hard drive, storage device, the cloud) [CPG 2.O, 2.R, 5.A].

- Require all accounts with password logins (e.g., service accounts, admin accounts, and domain admin accounts) to comply with NIST's standards when developing and managing password policies [CPG 2.B]. This includes:

- Use longer passwords consisting of at least 8 characters and no more than 64 characters in length;

- Store passwords in hashed format using industry-recognized password managers;

- Add password user "salts" to shared login credentials;

- Avoid reusing passwords;

- Implement multiple failed login attempt account lockouts;

- Disable password "hints";

- Refrain from requiring password changes more frequently than once per year.

Note: NIST guidance suggests favoring longer passwords instead of requiring regular and frequent password resets. Frequent password resets are more likely to result in users developing password "patterns" cyber criminals can easily decipher. - Require administrator credentials to install software.

- Use phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication (MFA) [CPG 2.H] (e.g., security tokens) for remote access and access to any sensitive data repositories. Implement phishing-resistant MFA for as many services as possible—particularly for webmail and VPNs—for accounts that access critical systems and privileged accounts that manage backups. MFA should also be used for remote logins. For additional guidance on secure MFA configurations, visit cisa.gov/MFA and CISA's Implementing Phishing-Resistant MFA Factsheet.

- Keep all operating systems, software, and firmware up to date. Timely patching is one of the most efficient and cost-effective steps an organization can take to minimize its exposure to cybersecurity threats. Prioritize patching known exploited vulnerabilities of internet-facing systems [CPG 1.E]. CISA offers a range of services at no cost, including scanning and testing to help organizations reduce exposure to threats via mitigating attack vectors. Specifically, Cyber Hygiene services can help provide a second-set of eyes on organizations' internet-accessible assets. Organizations can email vulnerability@cisa.dhs.gov with the subject line, "Requesting Cyber Hygiene Services" to get started.

- Segment networks to prevent the spread of ransomware. Network segmentation can help prevent the spread of ransomware by controlling traffic flows between—and access to—various subnetworks to restrict adversary lateral movement [CPG 2.F].

- Identify, detect, and investigate abnormal activity and potential traversal of the indicated malware with a networking monitoring tool. To aid in detecting the malware, implement a tool that logs and reports all network traffic, including lateral movement activity on a network. Endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools are particularly useful for detecting lateral connections as they have insight into common and uncommon network connections for each host [CPG 3.A].

- Install, regularly update, and enable real time detection for antivirus software on all hosts.

- Review domain controllers, servers, workstations, and active directories for new and/or unrecognized accounts.

- Audit user accounts with administrative privileges and configure access controls according to the principle of least privilege [CPG 2.D, 2.E].

- Disable unused ports [CPG 2.V, 2.W, 2X].

- Consider adding an email banner to emails received from outside your organization.

- Disable hyperlinks in received emails.

- Implement time-based access for accounts set at the admin level and higher. For example, the Just-in-Time access method provisions privileged access when needed and can support enforcement of the principle of least privilege (as well as the Zero Trust model). This is a process where a network-wide policy is set in place to automatically disable admin accounts at the Active Directory level when the account is not in direct need. Individual users may submit their requests through an automated process that grants them access to a specified system for a set timeframe when they need to support the completion of a certain task [CPG 2.E].

- Disable command-line and scripting activities and permissions. Privilege escalation and lateral movement often depend on software utilities running from the command line. If threat actors are not able to run these tools, they will have difficulty escalating privileges and/or moving laterally.

- Perform regular secure system backups and create known good copies of all device configurations for repairs and/or restoration. Store copies off-network in physically secure locations and test regularly [CPG 2.R].

- Ensure all backup data is encrypted, immutable (i.e., cannot be altered or deleted), and covers the entire organization's data infrastructure.

Ransomware Guidance

- CISA.gov/stopransomware is a whole-of-government resource that serves as one central location for ransomware resources and alerts.

- CISA, FBI, the National Security Agency (NSA), and Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC) published an updated version of the #StopRansomware Guide, as ransomware actors have accelerated their tactics and techniques since its initial release in 2020.

- CISA has released a new module in its Cyber Security Evaluation Tool (CSET), the Ransomware Readiness Assessment (RRA). CSET is a desktop software tool that guides network defenders through a step-by-step process to evaluate cybersecurity practices on their networks.

VALIDATE SECURITY CONTROLS

In addition to applying mitigations, CISA and FBI recommend exercising, testing, and validating your organization's security program against the threat behaviors mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK for Enterprise framework in this advisory. CISA and FBI also recommend testing your existing security controls inventory to assess how they perform against the ATT&CK techniques described in this advisory.

To get started:

- Select an ATT&CK technique described in this advisory (see MITRE ATT&CK's page on QakBot).[9]

- Align your security technologies against the technique.

- Test your technologies against the technique.

- Analyze your detection and prevention technologies performance.

- Repeat the process for all security technologies to obtain a set of comprehensive performance data.

- Tune your security program, including people, processes, and technologies, based on the data generated by this process.

CISA and FBI recommend continually testing your security program, at scale, in a production environment to ensure optimal performance against the MITRE ATT&CK techniques.

REPORTING

FBI is seeking any information that can be shared, to include boundary logs showing communication to and from foreign IP addresses, a sample ransom note, communications with QakBot-affiliated actors, Bitcoin wallet information, decryptor files, and/or a benign sample of an encrypted file. FBI and CISA do not encourage paying ransom, as payment does not guarantee victim files will be recovered. Furthermore, payment may also embolden adversaries to target additional organizations, encourage other criminal actors to engage in the distribution of ransomware, and/or fund illicit activities. Regardless of whether you or your organization have decided to pay the ransom, FBI and CISA urge you to promptly report ransomware incidents to a local FBI Field Office or CISA at cisa.gov/report.

RESOURCES

- HHS: Qbot/QakBot Malware

- CISA: CPGs

- NIST: 800-63B Digital Identity Guidelines

- CISA: MFA

- CISA: Implementing Phishing-Resistant MFA

- CISA: Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

- CISA: Cyber Hygiene

- CISA: Zero Trust

- CISA: #StopRansomware

- CISA: #StopRansomware Guide

- CISA: CSET Tool Sets Sights on Ransomware Threat

REFERENCES

- MITRE: Cobalt Strike

- MITRE: Conti

- MITRE: ProLock

- MITRE: Egregor

- MITRE: REvil

- MITRE: MegaCortex

- MITRE: Black Basta

- MITRE: Royal

- MITRE: QakBot

DISCLAIMER

The information in this report is being provided "as is" for informational purposes only. CISA and FBI do not endorse any commercial entity, product, company, or service, including any entities, products, or services linked within this document. Any reference to specific commercial entities, products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by CISA and FBI.

VERSION HISTORY

August 30, 2023: Initial version.

Source: Identification and Disruption of QakBot Infrastructure (https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-242a)